Wind Song was the ultimate dream boat of a Chesapeake Bay sailor named Bill Kay. Bill trained as a naval architect/marine engineer until his senior year in college, when he switched his major to Mechanical Engineering because he thought it might make him more employable in post-war America. Wind Song was his last boat, and he died about a month after we bought her from him.

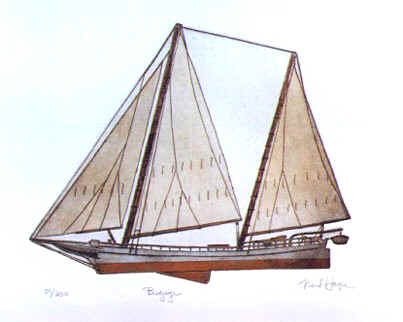

Wind

Song's design was based on the Chesapeake Bay "bugeye" oyster-dredging

ketches of the 1800's. These boats, which were typically 60-80

feet long, were shallow draft, internally ballasted, centerboard-equipped

sailing vessels, usually double-ended, with bottoms

made of rough-hewn, cross-bolted logs, and with plank-on-frame

sides built up from the log bottom, which was typically 9 to 13 logs wide

-- always an odd number, so the centerboard would not be located between

logs.

Wind

Song's design was based on the Chesapeake Bay "bugeye" oyster-dredging

ketches of the 1800's. These boats, which were typically 60-80

feet long, were shallow draft, internally ballasted, centerboard-equipped

sailing vessels, usually double-ended, with bottoms

made of rough-hewn, cross-bolted logs, and with plank-on-frame

sides built up from the log bottom, which was typically 9 to 13 logs wide

-- always an odd number, so the centerboard would not be located between

logs.To provide more working space aft, a so-called "patent stern", consisting of a rectangular platform built on top of the pointed aft end of the hull, was added in many cases. This also served as a base for the large, distinctive davits that served as a hoist for the yacht tender. The bugeyes themselves were not mechanically powered even in recent years, since, as oyster populations have diminished, it is now illegal to oyster-dredge under power in the Chesapeake.

The vessels were usually equipped with an outboard rudder on a slanted axis, as shown in the sketch. This gave the bugeye a rather severe weather helm, about which more later. The sail plan was invariably a spreaderless marconi ketch with a half-club self-tacking jib on a long "hogged" (slightly downward-curving) bowsprit. Photos of the Edna E Lockwood and the JC Armiger bugeyes are shown below.

Wind Song 's current dimensions are 52'6" overall including bowsprit and dinghy davits, 38' on deck, 30' on the waterline, 10'6" wide, and 3'2" deep unloaded with centerboard retracted, 7' with it extended. With the dinghy on the davits she grows to 54'. Loaded for cruising she'll draw about 3'4".

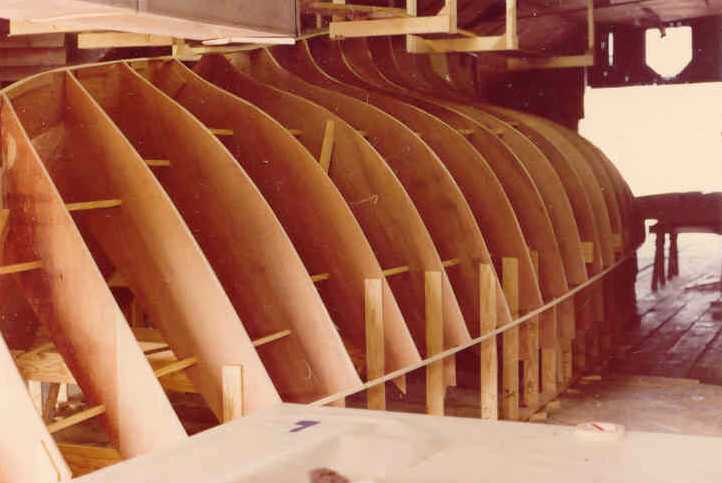

She was designed by Bill Kay. The engineering drawings were accomplished by Kaufman and Ladd in Annapolis, MD. She was laid up in solid fiberglass over a male frame-mold (see photos below). The layup began with a commercially available scrim called SeaFlex laid onto the upside-down mold and tacked in place. SeaFlex consists of longitudinal stringers of cured fiberglass/resin composite each roughly 1/2" wide by 1/10" thick, held together by a loose

crossweave of dry glass fibers. After

this material was in place, glass/resin layup proceeded outward to half

the design thickness. The whole mess was then flipped right side up, the

mold removed, and the inside layup completed. The inside of the hull was

left rough and painted, while the outside was ground smooth, faired with

putty, sanded smooth, and then painted.

crossweave of dry glass fibers. After

this material was in place, glass/resin layup proceeded outward to half

the design thickness. The whole mess was then flipped right side up, the

mold removed, and the inside layup completed. The inside of the hull was

left rough and painted, while the outside was ground smooth, faired with

putty, sanded smooth, and then painted.The photo below left shows the hull after the outer layup has been completed, and below right is the hull exterior after fairing.

These photos show the hull after painting the topsides.

This photo shows her emerging from the construction shed for launching, with the entire Kay family present.

Wind Song was originally designed to be 36 feet on deck with an outboard rudder on a slanted counter, which is how she appears above. As hinted earlier, in addition to the substantial inefficiency of outboard rudders in the first place this slant caused the rudder to try to bury the stern in the water when the rudder was steered to one side, causing tremendous resistance to the helmsman's effort, with the result that no one in Bill's family except Bill could steer the boat. His wife Peggy was particularly challenged. Historically bugeyes used outboard rudders for construction economy and hull integrity, and the helm resistance was less on the double-ended vessels, though still pronounced.

To rectify this unacceptable behavior, Bill commissioned a redesign and rebuild to a fully balanced inboard rudder on a vertical axis. This required the entire stern of the boat to be sawed off and a two foot extension added on (photos below). The result has been the almost complete elimination of steering effort until the boat has heeled so that the lee rubrail is in the water.

After all this, today the aft underbody looks like this:

And yes, the discerning eye will have recognized a bronze 3-blade MaxProp in front of the rudder, the best cruising sailboat propeller money can buy. We really have to thank Bill for this, and it is typical of the entire boat that he would have nothing but the best. It is exactly the prop Lane would choose if money were no object (which is almost never). That $3,000 marvel of engineering provides these advantages: 1) the propeller has the same hydrodynamic efficiency in reverse as in forward, 2) the pitch is adjustible to match the power characteristics of the motor perfectly, and 3) the blades feather to the water flow when the motor is off, presenting virtually zero drag. And since this prop operates free rather than encumbered in an aperture, it's design efficiency is actually achieved. With this prop and a 4-cylinder, 108 cubic inch, 40 hp diesel Wind Song motors at 7.1 knots with a hissing wake in flat water at 2400 rpm -- remarkable for a boat with a maximum theoretical hull speed of 7.34 knots -- yet under sail she handles as if there is no prop at all.