24° 23.71' N, 76° 37.95'

W

Warderick Wells Cay, Exuma Cays, Bahamas

Wednesday, December 8th, 2004

This cay is the home of the headquarters

of Exuma Cays Land and Sea Park, one of 25 Bahamas National Parks that are

administered by the Bahamas National Trust. This remarkable Park and organization

deserve substantial coverage on the Wind Song web site. No representation

of Bahamas cruising could be considered complete without it.

You can of course visit the Bahamas National

Trust web site. Some of

the material that follows came from there. But let's start with the following

statement:

The Bahamas

National Trust (BNT) was established by an Act of Parliament in 1959

as a non-governmental,

self-funded, statutory body,

mandated

with the development and management

of the National

Park System in The Bahamas.

That sentence might bear a second reading.

This is a private, self-funded organization that runs the

Bahamas National Parks by parliamentary mandate. It receives not one dime

from the government. It relies on private donations, with all the opportunity

for influence and corruption that implies. Its labor force is almost entirely

volunteer. It does not have the power of eminent domain. How can this possibly

work?

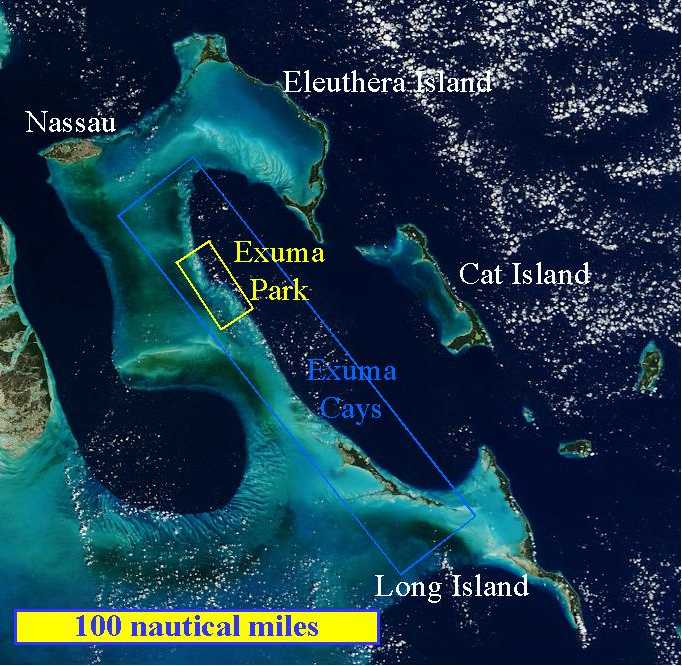

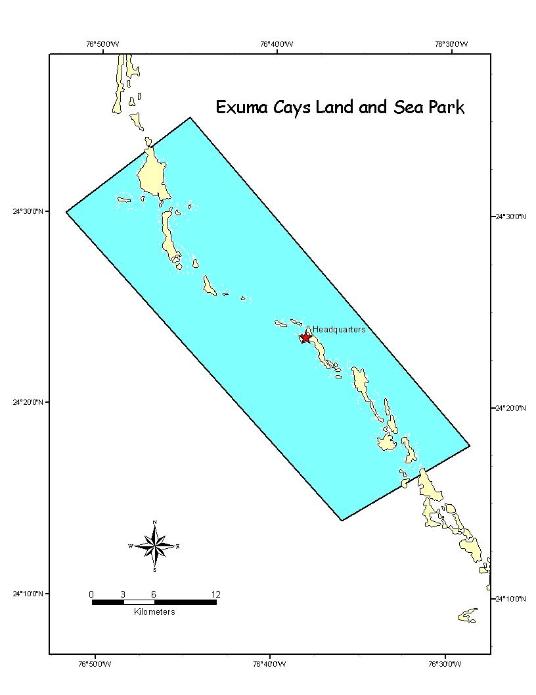

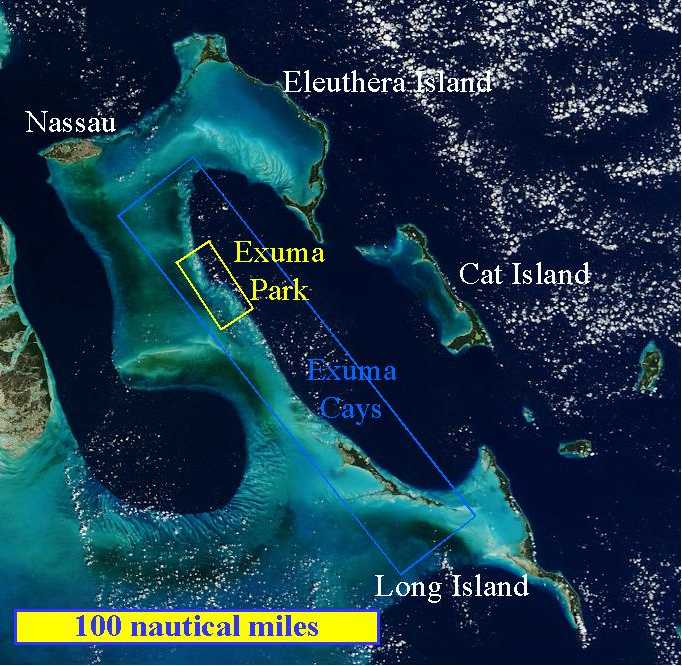

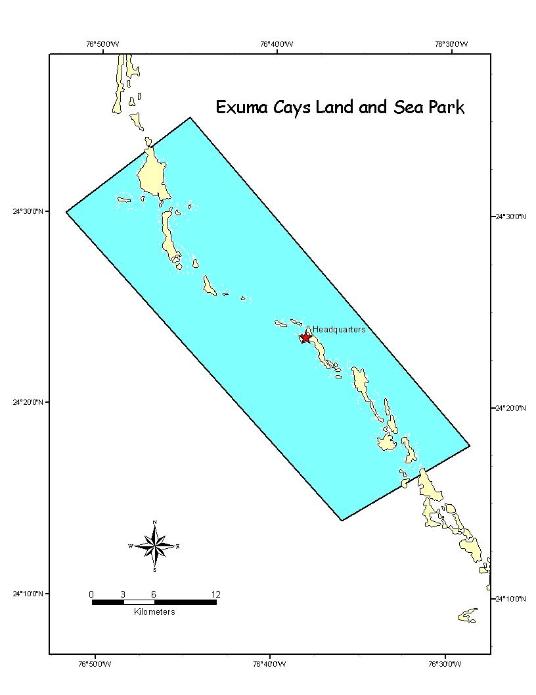

Yet it does, and the 8 by 22 mile Exuma Cays

Land and Sea Park is a great example. Exuma Park consists of six island groups,

each named for the main island in the group, to wit (NW to SE -- see photo

and map below): Shroud Cay, Hawksbill Cay, Cistern Cay, Warderick Wells, Hall's

Pond Cay, and Bell Island. The 8-mile width of the Park extends out onto

the shallow Great Bahama Bank to the west and into the deep Exuma Sound to

the east. Here's where it lies with respect to the rest of the Bahamas.

The Park was the original impetus behind the

1959 founding of the BNT. Put another way, the Bahamas National Park system

was founded so that there could be an Exuma Cays Land and Sea Park.

This is because the country had no money for a Park System at the time, so

there had to be something official on the books that said any Parks that got

created couldn't cost the country any money. Parliament put the Exuma Park

region under protection for one year in 1957 and gave the Park activists one

year to invent from scratch a no-cost way to run a national park system. In

1958 this was extended one more year, and in 1959 the deed was done. It is

astounding that a bureaucracy that forbidding could be circumvented that quickly.

Exuma Park still has exactly one paid employee,

the Park Warden, Ray Darville, who became Warden in February 1993

and has lived here and held this position very full time for the 11.5

years since. (Type "Ray

Darville Exuma" into Google and see what you get.) Ray is surrounded by a

small, constantly changing cadre of dedicated long term (6 months to 2 years)

volunteers who actually run the place, basically in exchange for free mooring

in the mooring field out in front of the HQ, where anchoring is not allowed

and the charge (for boats up to 40 feet) is $15 or 6 hours of labor per day.

More than that can get you free water, a place to tie up close to the office,

and electricity, or, for boatless volunteers, a bit of "crash-pad"-style

sleeping space ashore. The core group is supported by casual volunteer labor

donated by visiting yachties, who number in the hundreds through a cruising

season. These volunteers, and the work they do, are managed by the core group,

so Ray can concentrate on higher duties.

Ray's word is law here, but

he isn't particularly dictatorial. He can't be. There's no way he could micromanage

everything happening here even if he were around all the time, which he isn't.

He has to trust these folks to make the day-to-day decisions.

Ray's duties basically have

three parts: 1) protect the Park's natural resources, 2) develop the park

itself to support and encourage visitors, and 3) support those visitors when

they visit. He directs numbers (2) and (3) from something of a distance through

the volunteers, while staying very busy doing number (1) all by himself.

This is because only the Park

Warden is authorized to enforce the law. And the law here is YOU CAN'T FISH.

The Exuma Cays Land and Sea Park is what is known as a No Take Zone, the first

in the Caribbean area. That doesn't mean there are fishing limits, or species-specific

fishing seasons, or what have you. It means NO LIVING THING in the water

can be harmed or even be molested. Given that there are certain segments

of the Bahamian population who live on fishing and REALLY want to fish right

here, Ray has his work cut out for him.

The Bahamas have been pretty

thoroughly fished out, the Exumas being no exception, and in the Exuma area

the folks responsible mainly reside in the small town of Black Point a few

miles south of the park, where they support themselves by "subsistence fishing".

The problem is, "subsistence" to these folks involves not just consuming fish

as food, but also sale of fish to get money -- not a lot of money, but enough

to "subsist" in the modern world, where (for example) a land line phone call

costs $0.18/ minute and local cell phone calls cost $0.40/minute ($0.91 to

the US). According to the volunteers we've talked to, these people could

not care less about this Park. They will fish anywhere for anything that

will make them anyamount of money whatsoever. We hear a certain poverty in

that attitude, which makes the attitude understandable, even if not tolerable.

Before Ray Darville came to town, No-Take enforcement was less vigorous, and

fishing in Black Point was a $100,000 annual business, mostly from inside

the Park. Granted, that isn't much when spread across the 300-person population,

but it is certainly enough to decimate the Exuma Park fishery. Ray singlehandedly

shut it down, and continues to identify, arrest, and prosecute poachers zealously.

This has not endeared him to the Black Point citizenry. The legal penalties

are not slight.

The chief results are, first

that the fish and other aquatic life in the Park have rebounded to a remarkable

degree (more on that shortly), and second that Ray goes on his daily patrol

through the Park expecting to get shot. In response, the Bahamas National

Defence Force has recently assigned him a rotating two-man contingent of automatic-rifle-equipped

marines who join him on patrol. Ray is engaged in a small war here. After

speaking with Ray for a bit, one cannot help but wonder if part of why it's

gone this far is that this suits his sense of style. Ray is, frankly, fanatical.

That said, it is only fair to

note that the whole notion of a No Take Zone here is new and very unwelcome

to this latest of many Bahamian generations brought up to fish indiscriminately,

and it may just be that a fanatic is required to make it work. If so, Ray's

the man. Whatever the case, the results are astonishing. The conch population

density in Exuma Park is 31 times the average density outside the park,

and migration of conch out of the Park provides a harvest of several million

a year to these same fishermen. Crawfish tagged in Exuma Park have been found

repopulating Cat Island, 70 miles away and empty of crawfish for many years.

74% of the Nassau Grouper in the northern Exuma region come from Exuma Park,

and grouper tagged in the Park have been found off both North and South

Long Island 150 miles away. This is the beauty of No Take Zones that fishing

seasons and seasonal limits can't touch: it is literally foolproof, not

requiring deep thought or calculated management, it cannot fail, and no one

who is close to the fishing can deny that it is working because virtually

every fish they catch comes from the Zone. There are renowned native Bahamian

fishermen and sportfishing guides here who believe that every major island

or island group in the Bahamas should have its own "feeder" No Take Zone,

and it is hard to disagree -- even though the Black Point populace does.

As a direct result of this success

in Exuma Park, the Bahamian Government has instituted a nationwide policy

to protect 20% of the marine ecosystem for fisheries replenishment purposes.

Accordingly, the Department of Fisheries is establishing a system of Marine

Protected Areas for fisheries replenishment. The US Government used Exuma

Park as a model to establish no take areas in the Florida Keys Marine Sanctuary.

There has been widespread call from Bahamians generally for more national

parks “in their own backyards”. And ten new national parks were established

in 2002, doubling the size of the National Park System -- all still at no

cost to the government.

And what about Ray? It takes

a lot to live with a man who, when he goes to work in the morning, may not

come back that night. His wife left him, took their three boys, and returned

to Montana where life is less uncertain. He lives here now with a girlfriend

in a new Warden's residence funded and built by a generous group of 20 US

donors, and the old Warden's residence in the back of the Park office building

has been turned into a barracks for the marines who guard Ray's life and

act as the Bahamian authority that arrests the bad guys. Life here is physically

hard, logistically complicated, and intense.

He has obviously paid, and continues

to pay, a price. For the roughly 11 months of the year he's on duty, working

12-16 hours/day and on call 24/7. It is quite literally his whole life.

Any relationships he has are sort of along for the ride. On the plus side,

he wakes up every morning knowing he is going to meet and interact with people

that day who, because they want to kill him, because they have

wrapped their lives around his every move, because they monitor all

his radio communications so they'll have some hope of knowing where he is

and when he's going to be gone (so they can poach), are living, breathing

proof that he makes a difference. And what time he does not spend on

patrol he spends with people who, through their tireless volunteer efforts,

make it crystal clear how much this means to them and how much they want Ray

to be able to continue doing exactly what he does. We are among them. This

is why Roxanne spent two of her precious few days here weeding and making

trail signs, and Lynn is at this moment collecting and hauling bags of plastic

and glass flotsam from the endless supply on the windward (Sound) side of

the island a half mile back across the mangrove swamp to the HQ to be burned,

crushed, and buried.

It is worth asking at this point

how many of us have jobs that daily give us palpable, immediate, and continuous

positive feedback on our effectiveness. If we all had jobs like that, maybe

we'd all be fanatics.

Friday, December 10th, 2004

We (well, Lynn) appear to have

made something of a command decision to jump to Georgetown by the end of next

week so as to have a few shopping days before Christmas (and Christmas itself)

there, so this is our last day (and last Internet access) here in Warderick

Wells. The plan is to come back north in January and visit the spots we'll

miss (or have already missed) by jumping. Georgetown,

which is located about halfway down the NE shore of Great Exuma Island (the

very large, long, skinny island at the SE end of the blue "Exuma Cays"

box in the photo above), is about 73 nautical miles from here, the last 56

of which we'll try to do in a day.

So let's do a few photos of Warderick

Wells and wrap this up. Here's an overview from nearby Boo Boo Hill (at 19

meters altitude the high point on the island), showing (left to right) the

radio mast, the new Warden's Residence, a couple of low service buildings

(generator shed, workshop, crash pad shed), and the HQ building. The North

Anchorage, where the moorings are, is to the right.

These two lemon sharks hang

out off the end of the dinghy/patrol boat pier below the HQ because . . .

people FEED them! What kind of sense does that make? One guy we heard

of also liked to feed the resident four and a half foot barracuda, "Bubba".

After doing so one day, he got a sat-phone call aboard his trawler and sat

on his transom swim platform to talk, dangling his feet in the water. Bubba

thought it was another snack, and . . . an emergency evacuation to Staniel

Cay ensued, followed by 44 stiches.

Below left, Tania and Roxanne

look out at Daybreak on a mooring in Warderick Wells north anchorage,

Spring 1994. View is to the NW from the Park Headquarters building.

Below right, Tania leans up against

Mom in the same spot, December 2004. Tania is somewhat larger now.

__

__

Below left, the eastern arm of the anchorage

from the HQ building. Wind Song's mooring ball is in 15 feet of water.

She has five feet under her rudder. The water under the dinghy, hanging on

the aft davits, is two feet deep. These are steep-sided, narrow channels

with lots of current in them.

Below right, Wind Song and the shallows

nearby. In the foreground is a patch of nearly dry sand, where the four of

us played yesterday like kids in a wading pool.

__

__

View NNW from Boo Boo Hill across the top

of the anchorage. Below left, Spring 1994. Below right, December 2004. Both

are at low tide. Those small dots on the white area in the left photo are

people trying to land their dinghy across the sandy shallows and go for a

hike. The dinghy had to be anchored right where you see it, as the water was

only 6" deep and getting shallower.

__

__

(below left) On the hike

to Boo Boo Hill, the ground, as on all "solid ground" in the Bahamas, is

extremely porous limestone.

(below right) Large hermit

crabs abound around the HQ. The shell this one is in is three inches across.

__

__

In some places, the ground is

very "porous". This sink-hole is a young mini-version of the larger

"blue holes" like we saw on Andros Island.

__

__

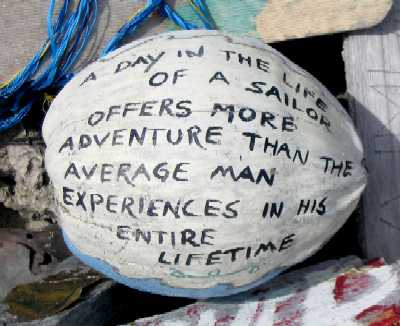

Boo Boo Hill is the one place

in Exuma Park where the "take only photos, leave only footprints" rule is

relaxed. Visitors may leave a memento of their visit, as long as it is biodegradable

in the marine environment -- because hurricanes often blow these mementos

into the surrounding ocean. If the sign on the Hill (lower left) that says

this isn't enough of an admonition, on the Park Headquarters landing beach

there is a full whale skeleton in front of which is a sign stating that the

whale died of plastic ingestion.

__

__

The view north (below left)

and southeast (below right) from Boo Boo Hill over Exuma Sound.

__

__

Late-breaking news: you remember

those Haitian trading sloops we saw in Nassau? We've also seen a lot of

them them sailing up and down the Great Bahama Bank west of the Exumas. They

actually sail pretty well. Turns out the naval arm of the Bahamas National

Defence Force makes a point of visiting each one it sees, to make sure everyone

on board is legal and is following all the rules, one of which is: no more

than four crew allowed (this is to minimize the opportunity for transporting

illegals). In the neighborhood of Exuma Park, the Warden helps out by investigating

any who sail by, if he's around at the time.

Right now he's not (he's on

vacation in Venezuela), but a naval patrol boat comes through here every

couple of days to tie up and catch some uninterrupted shut-eye. They patrol

the rest of the time, especially at night, when Haitian sloops that are carrying

illegals try to slip by the Park in the dark (and of course, without running

lights -- cuz they don't have any). One of them tried that last night . .

. and got caught. The patrol boat is here now, with the sloop's crew and

a half dozen illegals on board, all looking oh-so-glum.

We found out why. 1) They

all get deported, including the crew, legal or not, and none of them can

ever again be legal in the Bahamas. 2) The boat gets confiscated on

the spot and towed to a place off nearby Malabar Cays. 3) The spars

are stripped off, the wood mast gets cut off at the deck, falls in the water,

and all are transported to the Park HQ for use as building materials. And

4) the boat and all its contents are torched until the whole mess sinks.

We are told that there is nothing

aboard these boats except people, rice, water, and the most godawful stink

you have ever experienced.

Well, that's about all for this

report. Unless Glenn, the head volunteer up at HQ, wants Lane's help scuttling

the Haitian trader in the next day or two (we're told it's a labor-intensive

process), we'll be leaving in the morning for Little Bell Island with (oh

joy!) a full load of water.